Abstract

This qualitative study explored the determinants of women's employability in a developing country. The sample of 25 (N= 25) passed outs of the Government College of Technology for Women (GCTW) was selected through a purposive random sampling technique. The data were collected using a self-constructed interview protocol. The trustworthiness of the interview protocol was ensured through Maxwell's validity criteria and expert opinion. Thirteen (13) sub-themes and two major themes Determinants of employability and Determinants of women's employability were extracted from the data. The subthemes and major themes led to conclude this study. Determinants of employability and women's employability in a developing country have “skills” and “reputed colleges” as common determinants. GCTW is a unique institution, one of its kind. It is providing skills to young women and the placement cell in the institute is playing a vital role in placing their diploma holders in the market.

Key Words

Women Empowerment, Technical College, Developing Country

Introduction

Women's employability in developing countries has been a topic of great interest for researchers and policymakers. There have been significant improvements in recent years, but there are still many challenges that women face when it comes to finding and keeping a job in developing countries. In recent years, there have been a few constructive advances. To improve women's access to education and training, for instance, and to combat prejudice and discrimination in the workplace, several nations have put legislation and programs into place. Other measures, such as paid parental leave and flexible work schedules, have been involved by several nations to encourage work-life balance (Bin et al., 2020).

Work Integrated Learning (WIL) theory makes the theoretical framework of this study. Work-integrated Learning highlights the importance of a theory that integrates the individual, organizational, and societal dimensions of learning. The literature emphasizes the role of work-integrated learning in promoting employability skills, career development, and the development of transferable skills such as self-directed learning and metacognitive skills. Work-integrated learning is also seen as a way to promote social interaction and collaboration and to enhance social capital and cultural competence. According to a study by Billett, (2022), the importance of work-integrated learning as a way to promote students' development of skills and knowledge in real-world contexts is highlighted. The author emphasized the need for a theory of work-integrated learning that integrates the individual, organizational, and societal dimensions of learning. In a study by Jackson and Dean (2023), the authors proposed a work-integrated learning theory that emphasized the importance of self-directed learning and the development of metacognitive skills in real-world contexts. The theory highlights the role of work-integrated learning in promoting career development and enhancing employability skills. Similarly, a study by IJM Van der Heijden et al., (2019) explores the role of work-integrated learning in promoting career adaptability among young adults. The authors proposed a model of career adaptability that integrates work-integrated learning experiences and highlights the importance of self-directed learning and the development of transferable skills. In a study by Kettunen and Sampson (2018), the authors propose a work-integrated learning theory that highlights the importance of social interaction and collaboration in promoting learning and skill development. The theory emphasizes the role of work-integrated learning in promoting employability skills, social capital, and career development. A study by Dean et al., (2020) proposes a theory of work-integrated learning that integrates the personal, social, and cultural dimensions of learning. The theory highlights the importance of social and cultural contexts in promoting learning and skill development and emphasizes the role of work-integrated learning in promoting employability skills and career development.

The importance of Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in preparing individuals for active participation in functionally valuable jobs and as a reliable supply of skilled labour is acknowledged on a worldwide scale (Oviawe, 2018). Institutions that provide technical and vocational education and training (TVET) are crucial in preparing young people for the workforce and enhancing their prospects of employment throughout their careers. According to Jabarullah and Hussain (2019), TVET institutions adapt to the shifting demands of the labour market by adopting new training technologies, increasing the reach of their training, and enhancing the quality of all of their services, including governance, financing, teacher preparation, and industry collaborations. GCTW, the case chosen in this study is one of its kind college that provides young women with skills and direction to support themselves and ultimately contribute to the economy of the country. Skilled women can also move towards entrepreneurship and self-employment. In many contexts, entrepreneurship and self-employment offer important opportunities for women's economic empowerment and employability. Several studies have highlighted the importance of promoting entrepreneurship among women in developing countries, particularly in sectors where women are underrepresented (De Mel et al., 2013).

The current study concludes that skilled employed women have a positive effect on their lifestyle. They further contribute to improving the lifestyles of their family, ultimately playing a strong role economically and socially in a developing country. The study reveals that the strong determinants of women's employability in a developing country apart from skills are social pressures, gender biases, workplace timings, and everyday travel issues.

Objectives of the study

In the current study diploma holders (passed outs) from the Government College of Technology for Women (GCTW) were interviewed to find out the determinants affecting women's employability they experienced. Further, this study also explored the role of skills, attained through technology diplomas in the professional lives of young women who passed outs of GCTW.

Review of Literature

Recent studies underscore the ongoing challenges that women face in accessing and succeeding in the labour market in developing countries, highlighting the need for holistic, multi-faceted approaches that address a range of factors that impact women's employability.

Women's Employability in Developing Countries

A study by Kumar and Sinha (2022) in India found that women's employability is negatively impacted by social norms and gender biases that limit their access to education, training, and job opportunities. The study emphasized the need for policies and programs that address these gender biases and promote women's economic empowerment. In another study by Mgaiwa, (2021) in Tanzania, the authors found that women's employability is impacted by a range of factors, including lack of access to education and training, gender discrimination in the labour market, and social norms that limit their mobility and opportunities. The study calls for interventions that address these barriers to women's economic empowerment. Vu and Chi (2022) conducted research in Vietnam and found that access to education and training is a critical factor in improving women's employability in the country. The study also highlights the importance of addressing social norms and gender biases that limit women's access to employment opportunities. In a study by Singh and Kaur (2022) in India, the authors found that women face a range of challenges in accessing and succeeding in the labour market, including discrimination, lack of access to education and training, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. The study emphasizes the need for policies and programs that address these barriers to women's economic empowerment.

A study by Khidmat et al., (2021) in Pakistan found that women's employability is impacted by a range of factors, including discrimination in the labour market, lack of access to education and training, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. The study calls for policies and programs that address these barriers to women's economic empowerment, including affirmative action policies and training programs that promote gender equality.

Employability skills

Literature on women's employability skills

underscores the importance of providing training and skill-development opportunities that address the barriers that women face in accessing and succeeding in the labour market. These include lack of access to education and training, gender biases in the labour market, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. Policies and programs that prioritize women's access to training and skill-building opportunities can help to promote women's economic empowerment and improve their employability skills.

A study by Rawoof et al., (2019) in Pakistan found that women's employability skills are impacted by a range of factors, including lack of access to education and training, gender biases in the labour market, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. The study emphasizes the importance of providing training and skill-building programs that address these barriers to women's economic empowerment. In a study byAkpomi andIkpesu (2020) in another developing country Nigeria, the authors found that women's employability skills are critical for their success in the labour market, but that many women lack access to training programs that can help them build these skills. The study calls for policies and programs that prioritize women's access to training and skill-building opportunities.

A study by Anand et al., (2022) in India found that women's employability skills are impacted by a range of factors, including lack of access to education and training, limited opportunities for skill-building, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. The study calls for policies and programs that address these barriers to women's economic empowerment, and that prioritize women's access to training and skill-development opportunities. In a study by Hassan et al., (2020) in Pakistan, the authors found that women's employability skills are critical for their success in the labour market, but that many women lack access to training and skill-building programs that can help them build these skills. The study emphasizes the need for policies and programs that prioritize women's access to training and skill-development opportunities, particularly in sectors where women are underrepresented. Similarly, a study by Khan et al., (2021) in Bangladesh found that women's employability skills are impacted by a range of factors, including lack of access to education and training, gender biases in the labour market, and societal expectations around women's roles and responsibilities. The study calls for policies and programs that prioritize women's access to training and skill-building opportunities, and that address the social and cultural barriers which limit women's participation in the labour market.

Research Methodology

The study is qualitative. This researcher has adopted a phenomenology research design. Phenomenology is concerned with understanding the structures and experiences and how individuals perceive and make sense of the world around them (Neubauer et al., 2019). It emphasized the importance of attending to the details of individual experiences and the meanings that individuals attach to them, rather than focusing on external, objective realities. Phenomenological research often involves methods such as interviews, observations, and other forms of qualitative data collection (Van Manen, 2023). Twenty-five (25) passed-outs of GCTW were selected as samples for this study.

The data were collected through a self-constructed interview protocol. The trustworthiness of the interview protocol was validated through the Maxwell validity criteria. Two mock interviews were also conducted to ensure the reliability. Further two experts one a language expert and the other a qualitative researcher were asked to determine the validity and reliability of the interview protocol. Thematic analysis technique was used to reach the results of the study.

Data analysis

The passed-out diploma holders were interviewed face-to-face by the researcher. This part of the analysis provided empirical evidence of output given by the college (GCWU). A Quality supervisor (Nestle), Creative Associate, Designer, Sketcher (Sapphire), Stitching unit worker (DDM), freelancers (CIT), Style textile, and Wizzio software (Electronic diploma holder) are some of the prominent Graduated diploma holders work who are working to the satisfaction of their superiors.

Most of the diploma holders said that they were able to get a job within the period of 4 to 6 months after completion of their diploma. One of the participants however said, “…..It took me (one) 1 year to get the job based upon my degree…..” the participant said further that in the CIT the skills, technology, and theories are changing rapidly as compared to other fields so those have to be updated themselves apart from their academic education. A creative associate in a software company said that she was able to get a job within 2 to 3 months. A participant in this research, a DDM diploma holder working in a renowned garment company said, “…I got the job as soon as I completed my diploma ” Few of the participants said that they had the job options but they were unable to accept the job offers due to daily travel issues. Describing this a graduate said, “….. I had to wait for some time, as in…..(thinking) 5 months to get an appropriate job related to my academic diploma and skills….” PLC, switch circuit, and troubleshooting of the machine troubleshooting helped me to solve the issues. The technical terms I learned in the diploma and course helped me a lot to gather extra respect in the field due to my knowledge.

The workspace environment, time limitations, qualifications, and skills are identified by the diploma holders as determinants of women's employability. Most of the participants said that the skills that they get out of the academic diploma are not enough to get a job in the market. The employers do not trust the skills which we have gained during the completion of their diploma. Most of the participants of this study said that their knowledge helped them for the job but they lacked the required set of skills.

Most of the participants said that some of the companies offer pieces of training to diploma-holder students before they offer them the job. All the diploma holder students accepted the fact that their diploma was preferred to get them training. They expressed that they would not have been able to earn even training if they did not have the diploma. They further added that employers think that we have basic knowledge so we should be trained well. Few of the participants said, “Theoretical knowledge helped them adjust, get the training and job but they still lack skills” Most of the participants expressed that their skills do not fulfil the employer requirements. Almost all the employed diploma holders declared with confidence that because of their diploma, they were preferred over candidates without diplomas by the employers. Few of the candidates shared that jobs were not available even after earning a diploma as organizations do not hire fresh passed-outs (without experience). One of the participants (G20) said, “…….I realized that I got the job because I am a diploma holder from this particular college…..” Few more employed diploma holders stated that the placement cell of the college and placement officer of the institute (GCWU) helped them trace and get the job. A diploma holder shared the fact that organizations (employers) prefer passed outs of this college over others. One of the diploma holders expressed it by saying, “The employers trust our degree…..” All the interviewees said that as they are females, they feel that female employers help them to get the job more than male employers. More diploma holders expressed that they feel more comfortable with a flexible environment with more female workers at the workplace. One of the diploma holders said, “……if there are more females at the workplace I feel myself in comfort zone…..” one of the DDM passed outs said that she works in a co-environment (males and females) initially it was difficult for her to adjust but ultimately she got comfortable. A Graphic designer graduate shared that she works in a co-working space but she was mentally prepared to work with males. She said, “…..I knew the field I chose is male-oriented in terms of workspace,… hmmm however I feel that women are working more as freelancers in my field”.

The CIT and electronic diploma holders tend to depend more on pieces training and skill development after the completion of the diploma from the institute rather than the DDM diploma holders. The CIT and electronic diploma holders say that they have to combat the everyday change in technology and are bound to update their skills in that particular technology to keep up with the market pace as in on the other hand the DDM diploma holders because they say that they are very comfortable in using the same types of machinery in the market as made available by the college. DDM diploma holders also added that it is easy for them to get jobs based on their diploma however choosing an appropriate job for them takes time. CIT and electronic women diploma holders have to struggle to grab a job opportunity.

When questioned about the incentives based on the qualification of women diploma holders, only a few of them agreed that they receive incentives because of their diploma in a particular field. Most of the women diploma holders said that the incentives are part of the salary packages that are offered by a company nothing special is being offered to them. One of the diploma holders (G8) said, “ ….maybe I am a new entrant here yet that is why I am not offered any incentive….. but when they see my skills as a designer they will offer me an incentive or a bonus”. On the other hand, a graduate (G2) said, “Yes, I am offered an incentive because I possess a diploma in this field, the incentive is small but yes this diploma has gained me an incentive”. The diploma holders also divulged their pay structures with the researcher CIT and DDM diploma holders said that their salary packages lie between 15k to 25k Pakistani rupees and it increases annually. Further, DDM diploma holders said that some pay holidays are bonuses offered to them from time to time. Few CIT diploma holders said that they work freelance if they want to earn more and mostly they do not get paid leaves.

Result

Most of the diploma holders sounded satisfied with their academic diplomas gained from the college. They appreciated and gave a fair amount of credit to the college for helping them in the job hunt even after their diploma acquisition. The diploma holders voiced the fact that most of them are welcomed in the fields and are preferred over the normal diploma holders. Most of them said that they have more skills than other normal diploma holders. Normal diploma holders have only academic knowledge but diploma holders of GCUW felt that they also have a set of skills other than academic knowledge. The enrolled and passed-out diploma holders both voiced that they lack skills. The practical portion in the academic syllabus does have more weightage than the theoretical syllabus but the practical skills imparted are not in match with the market needs. Diploma holders agreed that they were able to get the job but they had to improve their skills to compete in the market.

CIT enrolled and diploma holders both discussed that the required advanced level soft wares not taught to them in the college. They lack the skill to work as required in the market. The enrolled students said that they cannot work as freelancers and diploma holders said that they did not get the required job due to a lack of skills, until and unless some company offered them training before getting their hands on a proper job. Similarly, the diploma holders of Electronics face the same problem that the equipment that they lean to deal with in college was old and when they got into the job market they had to deal with new electronic machinery they knew nothing about it. DDM students on the other hand feel satisfied regarding the training and machinery. The factor affecting their employability in this particular field is the workplace environment and timings.

The diploma holders thought that the practical approach at the college regarding curriculum, assessing the market need through seminars, and providing industrial tours had polished their skill set and made them learn different technologies.

Figure 1

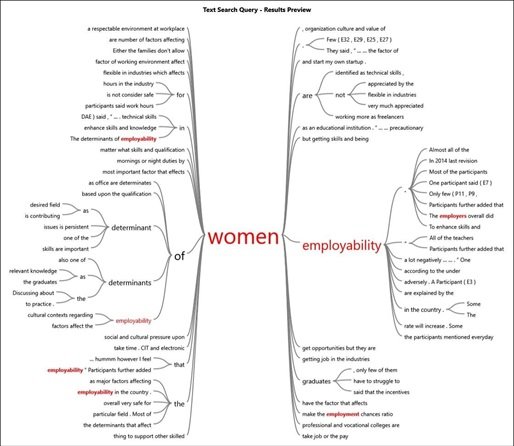

The data analysis results that all the graduated participants of this study are working with prestigious organizations. All of them credit the college for the learning experience that they have received. The placement cell and teachers of this college are highly appreciated by the diploma holders in the field and have found the learning very useful. The only factor that pass-outs emphasized that needs to be upgraded is the enhancement of skills. The diploma holders said that they have skills but they are not advance enough to cope with the market need. They suggested that the curriculum of the college (GCTW) needs to design curriculum for the future, not the present then only they will be able to prepare skilled diploma holders. Factors of women's employability are explored to be different from the determinants of employability. Women have to face social pressures, transport, and travel problems which are strong factors affecting women's employability according to the literature and the data. Similarly, the workplace environment is considered biased. According to this data, this affects women more than men and the impact is negative. Women do not feel safe at factories and while travelling for work at odd times. The word tree below shows this fact in the data.

Figure 3

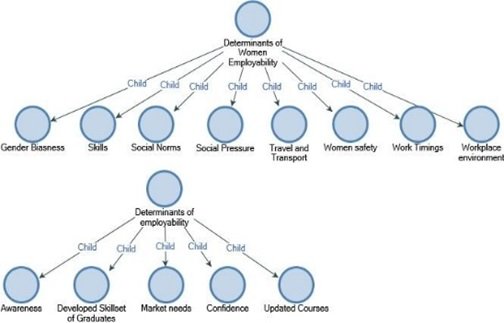

The mind map below displays the most important extracted result related to this research. The difference between Determinants of employability and determinants of women's employability is different. Skills are the only common determinant between employability and women's employability. The mind map extracted from advanced software beautifully shows the difference between node and child nodes. Most of the determinants affecting women's employability harm women's employability. Skills are the only determinant of women's employability imparting positive

impact. Institute under study is for sure imparting skills to women and contributing to making life better for them. Gender biases and social pressures create difficulties for working women and contribute as determinants of women's employability. Market need is one of the important themes identified as a factor of employability. Diploma holders and employers agreed upon the fact that the GCT (W) contributes well to meeting the market needs regarding employability.

Figure 4

The major themes and subthemes are derived from data. The themes and subthemes are represented with references in Table 1. The number of references in the table below represents the relative sentences and words in the interview data related to the major or subtheme. This table is downloaded from NVivo software used for the analysis of data

Table 1

|

Determinants of employability |

Major Theme |

1 |

1 |

|

Awareness |

Sub-theme |

1 |

1 |

|

Confidence |

Sub-theme |

1 |

4 |

|

Developed Skillset of diploma holders (Graduates) |

Sub-theme |

1 |

14 |

|

Market needs |

Sub-theme |

1 |

22 |

|

Updated Courses |

Sub-theme |

1 |

3 |

|

Determinants of Women's Employability |

Major Theme |

1 |

13 |

|

Gender Biases |

Sub-theme |

1 |

8 |

|

Skills |

Sub-theme |

1 |

7 |

|

Social Norms |

Sub-theme |

1 |

9 |

|

Social Pressure |

Sub-theme |

1 |

6 |

|

Travel and Transport |

Sub-theme |

1 |

7 |

|

Women safety |

Sub-theme |

1 |

7 |

|

Work Timings |

Sub-theme |

1 |

3 |

|

Workplace environment |

Sub-theme |

1 |

6 |

Conclusion

This study concludes that work integration

learning is playing a part in women's employability. They can earn and improve the quality of lifestyle of their families and themselves. Further, this study concludes that determinants of employability mostly differ from determinants of women's employability. The two common determinants between both are “skills” and “reputed institution”. Skilled women diploma holders are not working in fields due to factors like social pressure, work timings, and workplace gender biases rather than not having skills. Women diploma holders of GCTW can get jobs within 1-6 months which is appreciable.

Discussion

Institutions that provide technical and vocational education and training (TVET) are crucial in preparing young people for the workforce and enhancing their prospects of employment throughout their careers. As the requirements of the labour market change, TVET institutions adapt by implementing new training technologies, increasing the reach of their training, and enhancing the quality of their services across the board, including in governance, finance, teacher preparation, and industry collaborations (Jabarullah & Hussain, 2018). In addition to supporting students in improving their quality of life through gainful work, the role of the teacher in technical and vocational skill development training programs given across the country contributes to the nation's social and economic progress. These skills contribute to the nation's economic growth by increasing individual incomes, potential career progression, and employability (Bin et al., 2020). The current study provides empirical proof by concluding from the collected data that GCTW diploma holders' abilities enable them to make a good livelihood for themselves and their families. Their wages help to improve their and their families' standard of living. One of the current study's findings is that timings and social problems are determinants of women's employability. This aligns with the findings of a research study conducted by Kim and Tamborini (2019), who concluded that working women are more affected by timings, and social norms such as time of marriage, time of motherhood, and all related issues. One of the primary contributions made by this study to the existing literature is the examination of the differences between "Determinants of Employability" and "Determinants of Women Employability." The factors influencing women's employability were more closely tied to cultural and societal forces. Gender prejudice and non-flexible working hours at work had a larger role than the talents women have to work in a specific

industry. A decent income is not the main determinant of employment quality. Non-wage employment features like flexibility and job safety were also essential (Park et al., 2021).

Recommendations

1. The placement cell and placement officer of GCTW can trace out companies that provide transport services to the employees to facilitate women diploma holders.

2. The young women may be trained to work with the opposite gender so young women may get flexible, mentally and physically prepared for the male-dominated workplace environment.

3. Further research with more extensive data may be conducted to know the employer’s perspective regarding women's skills in the fields.

References

- Akpomi, E. M., &Ikpesu, O. C. (2022). Global Practices in Vocational Education and Emergence of Latent Entrepreneur-Based Businesses in Rivers State. Rivers State University Journal of Education, 25(2), 96- 107.

- Anand, I., &Thampi, A. (2022). India’s Employment Challenges: An Overview. South Asia Issue Paper, 15(1), 1-12.

- De Andrade, G. H., Bruhn, M., & McKenzie, D. (2013). A Helping Hand or the Long Arm of the Law? Experimental Evidence on What Governments Can Do to Formalize Firms. The World Bank Economic Review.

- Billett, S. (2022). Promoting Graduate Employability: Key Goals, and Curriculum and Pedagogic Practices for Higher Education. In Graduate Employability and Workplace-Based Learning Development: Insights from Sociocultural Perspectives (pp. 11-29). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Bin, E., Islam, A. A., Gu, X., Spector, J. M., & Wang, F. (2020). A study of Chinese technical and vocational college teachers’ adoption and gratification in new technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2359– 2375.

- De Mel, S., McKenzie, D., & Woodruff, C. (2013). The Demand for, and Consequences of, Formalization among Informal Firms in Sri Lanka. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(2), 122–150.

- Dean, B. A., Yanamandram, V., Eady, M. J., Moroney, T., & O’Donnell, N. (2020). An institutional framework for scaffolding Work-Integrated learning across a degree. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 17(4), 80–94.

- Griffin, M., & Coelhoso, P. (2019). Business students’ perspectives on employability skills post internship experience. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(1), 60–75.

- Van Der Heijden, B., Blanc, P. M. L., Hernández, A., González-Romá, V., Yeves, J., & Gamboa, J. P. (2019). The importance of horizontal fit of university student jobs for future job quality. Career Development International.

- Jabarullah, N. H., & Hussain, H. I. (2019). The effectiveness of problem-based learning in technical and vocational education in Malaysia. Journal of Education and Training, 61(5), 552–567.

- Jackson, D., & Dean, B. A. (2023). The contribution of different types of work- integrated learning to graduate employability. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(1), 93-110.

- Kettunen, J., & Sampson, J. P. (2018). Challenges in implementing ICT in career services: perspectives from career development experts. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19(1), 1–18.

- Khan, M. A. (2022). Livelihood, WASH related hardships and needs assessment of climate migrants: evidence from urban slums in Bangladesh. Heliyon, 8(5), e09355.

- Khidmat, W. B., Habib, M. D., Awan, S., & Raza, K. (2021). Female directors on corporate boards and their impact on corporate social responsibility (CSR): evidence from China. Management Research Review, 45(4), 563–595.

- Kim, C. and Tamborini, C.R., 2019. Are they still worth it? The long-run earnings benefits of an associate degree, vocational diploma or certificate, and some college. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 5(3), pp.64-85.

- Mgaiwa, S. J. (2021). Fostering Graduate Employability: Rethinking Tanzania’s university practices. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110067.

- Neubauer, B., Witkop, C., & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97.

- Oviawe, J. I. (2018). Revamping Technical Vocational Education and Training through Public-Private Partnerships for Skill Development. Makerere Journal of Higher Education, 10(1), 73-91.

- Park, J., Pankratz, N., &Behrer, A. (2021). Temperature, workplace safety, and labour market inequality.

- Rawoof, H. A., Ahmed, K. A., & Saeed, N. (2021). The role of online freelancing: Increasing women empowerment in Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Recovery Bus. Continuity, 12, 1179- 1188.

- Singh, N., & Kaur, A. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic: Narratives of informal women workers in Indian Punjab. In The Political Economy of Post-COVID Life and Work in the Global South: Pandemic and Precarity, pp. 17-50. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Sinha, D., & Kumar, P. (2020). Trick or Treat: Does a Microfinance Loan Induce or Reduce the Chances of Spousal Violence against Women? Answers from India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

- Van Manen, M. (2023). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Taylor & Francis

- Vu, N. T., & Chi, D. N. (2022). Vietnamese University Students’ Motivation and Engagement with Participating in Extracurricular Activities to Develop Employability (pp. 227–244).

Cite this article

-

APA : Muzaffar, S. M., & Rashid, K. (2023). Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country. Global Educational Studies Review, VIII(I), 330-340. https://doi.org/10.31703/gesr.2023(VIII-I).29

-

CHICAGO : Muzaffar, Syeda Maryam, and Khalid Rashid. 2023. "Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country." Global Educational Studies Review, VIII (I): 330-340 doi: 10.31703/gesr.2023(VIII-I).29

-

HARVARD : MUZAFFAR, S. M. & RASHID, K. 2023. Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country. Global Educational Studies Review, VIII, 330-340.

-

MHRA : Muzaffar, Syeda Maryam, and Khalid Rashid. 2023. "Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country." Global Educational Studies Review, VIII: 330-340

-

MLA : Muzaffar, Syeda Maryam, and Khalid Rashid. "Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country." Global Educational Studies Review, VIII.I (2023): 330-340 Print.

-

OXFORD : Muzaffar, Syeda Maryam and Rashid, Khalid (2023), "Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country", Global Educational Studies Review, VIII (I), 330-340

-

TURABIAN : Muzaffar, Syeda Maryam, and Khalid Rashid. "Determinants of Women Employability: Case Study of a Technical College in a Developing Country." Global Educational Studies Review VIII, no. I (2023): 330-340. https://doi.org/10.31703/gesr.2023(VIII-I).29